The medical and scientific literature is replete with graphical data that is rarely seen by the general public. This is unfortunate as “a graph is worth 1,000 words.”

I will present several graphs in which “time” (age, duration since an event) is on the X-axis and “the percent of people who are still alive” is on the Y-axis. This type of graph is called a Kaplan-Meier Survival graph and it can provide insights into human physiology and diseases.

I will focus on parameters that have been found to impact longevity, including:

If you are interested in a particular topic, click on the item above. If a displayed graph is too small, click on the graph to enlarge it.

Many of the graphs will demonstrate a statistically significant “correlation” between two things, such as the partaking in a behavior (excessive drinking, exercise, eating a lot of junk food) or having a disease (high blood pressure, depression) which I will collectively refer to as “Event-A” and a health outcome such as death “Event-B”. To say that Event-A and Event-B are “statistically correlated” means that Event-A and Event-B occur at the same time more frequently than would be expected by pure chance. When we learn that two events are correlated, it sometimes results in a better understanding of “how the world works.”

Let us begin with a simple Kaplan-Meier Survival graph of Americans’ longevity.

The Kaplan-Meier Survival Graph

This is a classic Kaplan-Meier survival graph. On the X-axis is a person‘s age and on the Y-axis is the percent of the initial population that is still alive.

This graph is based on Social Securities 2024 actuarial life table and predicts the survival of someone born in 2024.

At birth, 100% of the population is alive. As people get older, some will succumb to disease and accidents and the percent of the surviving population decreases.

The graph shows that at every age, a higher percent of females are alive than males. An explanation as to why females live longer than males, can be found on the website Our World Data, which has innumerable interesting graphs.

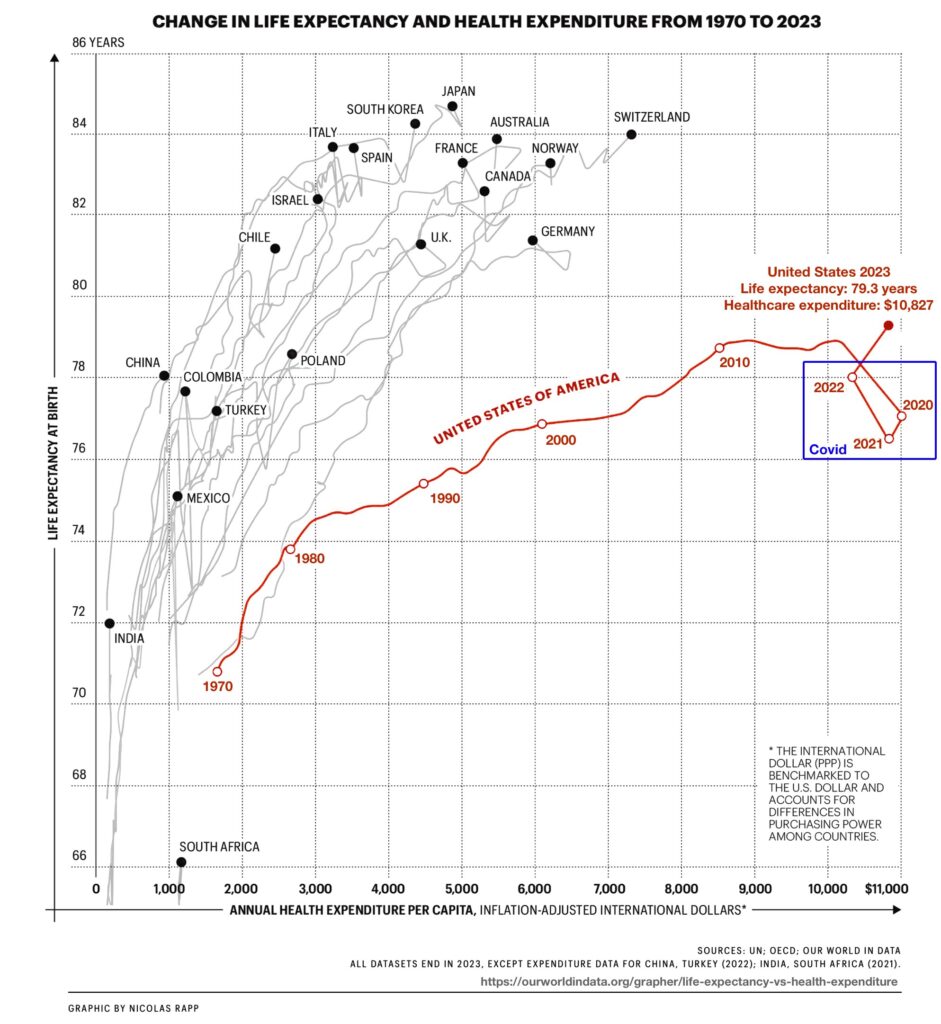

Well known to America’s medical community, but less well understood by the general public, is the fact that the United States has the highest per capita spending on healthcare despite having the lowest life expectancy among the industrialized countries.

There are different ways to assess the effect of a person’s weight (mass) on their health and longevity. We are going to look at two assessments, body mass index (BMI) and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR).

Body mass index is a simple calculation based on a person’s height and weight. It has been used for a long time as a method to predict a person’s health as a function of their weight, but it is an imperfect measurement, albeit useful in many situations.

In this Kaplan-Meier survival graph, 1,248 participants were divided into three groups based on their initial BMI:

Obesity Body Mass Percent Alive at Classification Index at End of Study not obese 18.5-29.9 85% mild obesity 30.0-34.9 84% moderate-severe ≥ 35% 80%

The study determined that the risk of death was nearly twice as high in the moderate-severe obesity group when compared to the ‘not obese’ group, but even mild obesity statistically increased the risk of death.

Another way to look at the data is to plot the BMI vs hazard ratio (HR); a hazard ratio is a person’s risk of dying compared to a person of a pre-specified BMI. In this study of 387,672 UK adult participants, a person with a BMI=25 was defined as having a hazard ratio of 1. The graph shows that a person with a BMI of 35, has an HR of about 1.7. This means that their risk of dying is 1.7 times the risk of death of (or 70% higher than) a person with a BMI of 25.

Clearly, the higher the BMI, the greater the risk of death.

These graphs, published in “Impact of Healthy Lifestyle Factors on Life Expectancies in the US Population,” provide additional insight into the impact of excessive weight on a person’s longevity. We will return to this publication several times.

Numerous medical studies have demonstrated that if a person intentionally loses as little as 5% of their weight, their risk of obesity-related diseases will decrease, and their longevity will increase. While dieting and keeping the weight off is only successful in the minority of dieters, the medical profession now has excellent weight-loss medications which result in substantial (10-20%) weight loss. Although there is still much that the medical profession does not know about the longterm ramifications of these new weight-loss medicines, they have been proven to reduce a person’s risk of getting obesity-related diseases and increase longevity.

Another way to assess the effect of a person’s weight on their health is the waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), which is sometimes a better measure than the BMI to assess the health effects of one’s weight. It is known that a 5% decrease in the WHR results in health benefits.

Here is the Kaplan-Meier graph of survival versus waist-to-hip ratio.

The study population is 418 community dwelling Brazilian who were at least 60 years old. The population is divide into thirds based on their gender average WHR. Men and women who are more robust and whose WHR was in the top 33% of their gender (men WHR ≥ 0.96, women WHR ≥ 0.85) are plotted in red while the slimmer 67% of the population (men WHR < 0.96, women WHR < 0.85) are plotted in blue. Again we see that the more robust population, with the higher WHR have a lower survival rate than the population with the smaller WHR.

A “hazard ratio” (HR) is yet another way to assess the impact of a person’s waist-to-hip ratio on their longevity. The HR is the risk of dying for a given waist-to-hip ratio divide by the risk of dying for a pre-defined “ideal” waist-to-hip ratio.

In this very large British study, a person with waist-to-hip ratio of 1.2 (blue dashed lines) has a four times the risk of dying as a person with the ideal waist-to-hip ratio of 0.87 (HR=1) shown in the green dashed lines.

The hazard ratio graph clearly demonstrates that the higher the waist-to-hip ratio, the greater the risk of death.

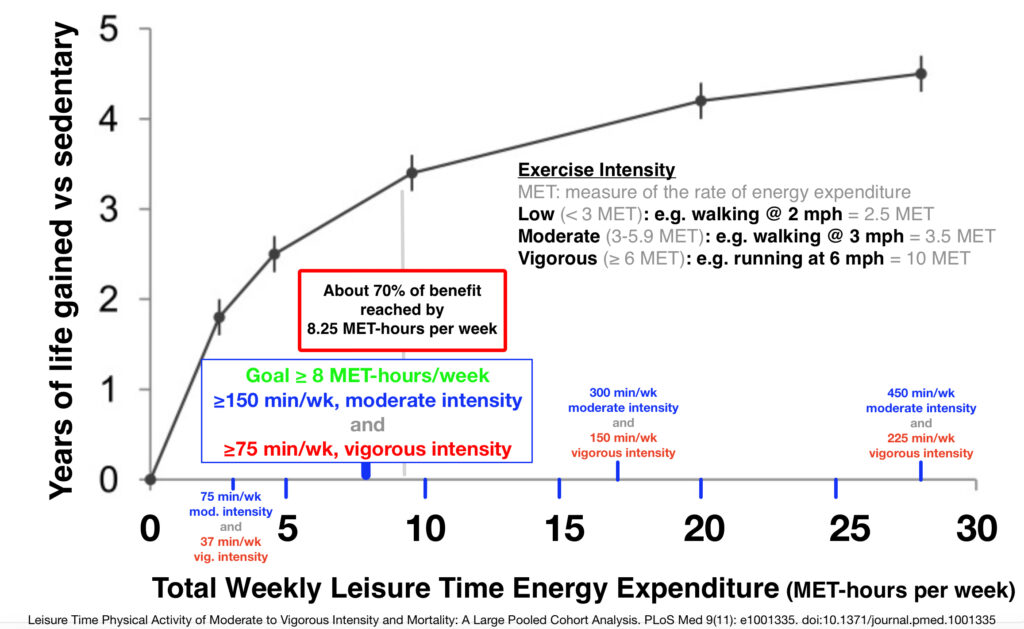

These two graphs demonstrate that people aged 50 years or older who exercise live longer than those who do not exercise. The data also show that the incremental increase in longevity is proportional to the total number of hours a week spent exercising.

Other studies have demonstrated that the magnitude of exercise-induced health benefits correlates with the intensity of the exercise.

In summary, the longer the exercise duration and the more intense the exercise, the greater the health benefits.

The data is clear that the largest incremental health benefit from exercising occurs when a “couch potato” begins a daily walking routine totaling 150 minutes a week. This can be achieved by walking:

-

- 22 minutes daily

- 30 minutes five times a week

- 50 minutes three times a week

- 75 minutes twice a week

As the data below demonstrates, there is no age limit when it is “too late” to begin an exercise routine–starting at any age will have a health benefit.

The next graph shows the impact of walking on longevity. If the goal is to maximize longevity while minimizing exercise time, one should ensure they have about 7,000 – 9,000 steps every day, which is equivalent to about 3 – 5 miles. (Note: In the below graph, “CVD” is cardiovascular disease or heart disease.)

Here is one final graph showing the relationship between exercise and increased longevity. Current guidelines recommend we exercise so as to expend the energy equivalent of at least 8.25 METs-hours each week, as this will increase our longevity to 70% of the maximum increment that could be achieved by exercising.

If one exercises by slowly walking at 2 mph (an energy expenditure rate of 2.5 MET) , you would have to walk 200 minutes every week to expend a total 8.25 MET-hours. If one walked at 3 mph (an energy expenditure rate of 3.5 MET), you would need to walk for 140 minutes every week and if one jogged at 6 mph (an energy expenditure rate of 10 MET) you would need to jog about 50 minutes a week.

The numbers shown in the graph and in the guidelines do not precisely align with the aforementioned time intervals given the imprecision of the energy expenditure rate of the various activities and the broad range of energy expenditure values that is inherent in the definition of low (< 3 MET), moderate (3-5.9 MET), and vigorous (≥6 MET) exercise intensity.

For additional information about exercising visit CDC Exercise Guidelines.

A Kaplan-Meier survival graph is the ideal method to understand the impact of smoking on longevity.

About 80% of men who never smoked will be alive at age 70, while only ~60% of male smokers will be alive at age 70. For those men who have permanently quit smoking, this number is ~75%.

Smoker have an increased probability of many disease, but lung cancer is particularly pernicious as the 5-year survival is only 14%.

We now know that if a smoker reduces their cigarette consumption by 50% they will“significantly reduces the risk of lung cancer” and death. If a smoker quits for about a decade their new risk of getting lung cancer begins to approach the risk of people who never smoked.

The below Kaplan-Meier survival graph would suggest that there may be a longevity benefit for the smoker to quit smoking at any age, up until age ~95 (men) and age ~90 (women).

On the prior page, we saw a Kaplan-Meier survival graph that showed that smoking cigarettes was associated with a reduction in longevity.

In these graphs, we can see that the cigarette associated reduction in longevity is proportional to the number of cigarettes a person smokes every day.

For example, a 50-year-person who smokes 1 pack-a day (20 cigarettes per pack) can expect to live about 8-9 years less than a non-smoker.

If that 50 year old, 1 pack-a day smoker, reduced their cigarette consumption to half-a-pack per day, their reduction in longevity, compared to a non-smoker would be about 6-7 years – by decrease the number of cigarettes they smoke would increase their longevity by about 2 years.

On the other hand, if that 50 year old, 1 pack-a day smoker completely quit smoking, their longevity would only be about 3 years less than the longevity of the non-smoker.

Again, the data is clear, the smoker who stops or reduces their cigarette consumption will incur an incremental longevity benefit, regardless of their age when the reduce their cigarette consumption – it is never too late to stopping smoking.

It has long been known that drinking excessive amounts of alcohol is unhealthy.

In the latter part of my professional career, research suggested that regularly drinking small amounts of alcohol conferred some health benefits. This conclusion was predicated on the assumption that research scientists had accounted for all “confounding variables”—factors that could influence the relationship between alcohol consumption and mortality.

However, newer, more sophisticated analytic methods that incorporate genetic information which are designed to account for unidentified confounding variables and “reverse causality” have overturned the prior understanding that drinking small amounts of alcohol was healthier than complete abstinence.

A study conducted in Great Britain, involving 278,093 participants, found that there is a “linear” relationship between alcohol consumption and the risk of death—“linear” means that the less alcohol consumed, the lower the risk of death—specifically, drinking even small amounts of alcohol increased one’s health risk when compared to abstinence and there was no benefit from drinking small amounts of alcohol. This is shown in the lower left corner where a person who drinks 0 (zero) drinks/day (green arrow) has an odd ratio (risk of death) even less than the person who drinks one drink/day.

If one wants to maximize their longevity, they should not drink any alcohol.

Sorry for the bad news!

High blood pressure–hypertension–is a common medical condition affecting nearly half of American adults. Unfortunately, only 22% of people with hypertension have their blood pressure appropriately treated. When untreated or poorly controlled, hypertension, the “silent killer,” significantly increases the risk of kidney disease, stroke, heart disease, blindness, and death.

The Kaplan-Meier survival graph below shows that individuals with poorly controlled high blood pressure are at substantially higher risk of premature death compared to those with normal or well-controlled blood pressure.

Bottom line: Have your blood pressure measured annually. If you have hypertension, ensure your treatment meets current medical guidelines.

In a clinical study called the “Alternative Healthy Eating Index and Mortality Over 18 Years of Follow-Up: Results From the Whitehall II Cohort,” 7,319 adults had a the quality of their diet measured and each was assigned an AHEI diet score that was based on their consumption of vegetables, fruit, nuts and soy, the ratio of white (seafood and poultry) to red meat, cereal fiber, trans fat, polyunsaturated-to-saturated fatty acid ratio, long-term multivitamin use, alcohol intake, and total fiber.

The study population was then divided into three groups according to their AHEI diet score—high-quality diet, average-quality diet, and low-quality diet—and followed for 18 years.

After adjusting the data for known confounding variables (factors known to influence mortality), the Kaplan-Meier survival graph shows that the top third of the population with the highest-quality diet lived the longest, while those with the lowest-quality diet had the shortest survival.

In comparison to eating a very poor quality diet, eating a high quality diet resulted in a 25% reduction in all-cause mortality and a 40% reduction in the risk of heart-related death.

Diet Quality: Years of Life Gained

In “Impact of Healthy Lifestyle Factors on Life Expectancies in the US Population” research scientist calculated the “Years Gained in Life Expectancy” by improving the quality of a person’s diet. As shown in the below graphs, a 50 year old man who had the lowest quality diet (AHEI-Q1) might live 4 years longer if he switched to the highest quality diet (AHEi-Q5), while a 50 year old women could expect to gain 5 years of longevity.

Robust data demonstrates that sleeping fewer than 6 hours or more than 9 hours per day is associated with increased mortality.

In this study of 1,494 community-dwelling adults (≥ 40 years old), sleep quality was assessed using a standard, validated sleep analysis. The study population was divided into two groups based on their sleep quality: “Good sleep quality” and “Poor sleep quality.”

As shown in the below Kaplan-Meier survival graph “individuals with poor sleep quality at baseline were 1.38 times more likely to die compared to those with good sleep quality”.

As this study was conducted in a rural Ecuadorian population, its conclusions may not be relevant to people living in a modern industrialized society.

Twenty-three percent of adult Americans (2022) reported a mental health disorder while 18.5% of adult Americans (2019) reported having depressive symptoms: mild (11.5%), moderate (4.2%), or severe (2.8%).

In the below Kaplan-Meier survival graph we see that people who have mild, moderate, or severe depression are more likely to die prematurely than people who have no or only minimal depressive symptoms. Fortunately, there are many treatment options for depression.

If you or someone you know is experiencing a psychiatric crisis, help is available. Here are hotline numbers for immediate assistance:

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (U.S.) Available 24/7 Dial 988 or 1-800-273-TALK (1-800-273-8255) Provides confidential support for anyone in distress, including a psychiatric crisis. Crisis Text Line Available 24/7 Text HOME to 741741 Free support via text messaging for anyone in crisis. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Helpline (24/7) Call 1-800-662-HELP (1-800-662-4357) Offers confidential assistance for mental health or substance use issues. Emergency Services If the situation is life-threatening, call 911 and inform them it’s a mental health crisis so they can dispatch appropriate assistance.

For several decades, healthcare professionals and social scientists have documented that a person’s socioeconomic status impacts their health. The below Kaplan-Meier survival graph shows that people who are in the lowest, most deprived, socioeconomic group have the highest mortality while those in the highest socioeconomic group have the lowest mortality.

In the graph below, a population who live in Great Britain were divided into five socioeconomic groups. Q1 is the most deprived, socioeconomic class, Q3 is middle-class, and Q5 is the highest, upper, least deprived, socioeconomic class. The authors then calculate the risk of dying, by age and socioeconomic group, for eleven diseases. The data clearly demonstrates that people in the lowest socioeconomic class have the highest probability of dying for every disease; dementia may be the sole exception. (Note: “Ischaemic heart disease” is the medical terminology for a heart attack.)

The death rate from air pollution in America has been consistently decreasing since 1990. Hurray!

The graph below shows that air pollution is most deadly to the elderly—their air pollution-induced mortality rate of 93.9 per 100,000 is higher than that of all other age groups.

It was not surprising to me that all of the above impact a person’s longevity.

Conversely, I was very surprised to learned that:

also impact a person’s longevity.

Meaningful Social Relationships

“Social Relationships and Mortality Risk” was a very large meta-analysis that included 148 studies and 308,849 participants, followed for an average of 7.5 years.

The research scientists found “Stronger social relationships were associated with a 50% increased chance of survival over the course of the studies, on average” and the magnitude of the benefit is comparable to quitting smoking and exceeds the impact of obesity, physical activity, and alcohol abstinence. When half of the participants in the study would have died, there will be 5% more people alive in the stronger social relationships group than the weaker social relationships group.

As Kurt Vonnegut said in 1978:

“We are so lonesome so much of the time because we were meant to live in extended family. To have dozens or even hundreds of relatives nearby, do what you can to get yourself extended families, no matter how arbitrary they may be. We all need more people in our lives and they do not have to be high-grade people either they can be imbeciles, [is] what matters is numbers good.”

Since the 5th–4th century BCE, the great minds of Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Confucius, Buddha, and others have reflected on the meaning and importance of “a sense of purpose and meaning in life.”

While there are many interpretations of this concept and no agreement on its precise definition, most agree it is important. For my own purposes, I define “a sense of purpose and meaning in life” as follows: “The individual believes they have lived a life that meets their own expectations (meaning) and gives them a reason to look forward to tomorrow (purpose).”

This abstract concept has also been explored in empirical research.

The study “Association Between Life Purpose and Mortality Among US Adults Older Than 50 Years” enrolled 6,985 adults over 50 years old. At the time of enrollment, participants completed a psychological questionnaire designed to measure their sense of life purpose. Based on their scores, participants were divided into quintiles.

The Kaplan-Meier survival graph below shows that people with the highest life purpose score (orange line) had significantly greater survival rates compared to those with the lowest score (dark green line). This finding has been corroborated in other clinical trials.

As the data is clear, if you do not already have a “life purpose,” it is in your interest to spend some time finding one. If you are uncertain how to do so, google “How do I find my purpose in life” or ask ChatGPT.

In America, there is a stigma to being “old.” Research suggests that this stigma can objectively reduce a person’s lifespan.

This phenomenon was studied and quantified in the paper “Longevity Increased by Positive Self-Perceptions of Aging.”

At the start of the study, 660 participants (98% Caucasian, aged 50–94) completed a psychological test designed to assess their “self-perceptions of aging”. Each participant received a score between 0 and 5, with higher scores reflecting more positive views of aging. Based on these scores, participants were divided into two groups—those with above-average and below-average self-perceptions—and were followed for up to 23 years.

After controlling for variables such as age, functional health, gender, and socioeconomic status, the researchers discovered that: “older individuals with more positive self-perceptions of aging, measured up to 23 years earlier, lived 7.5 years longer than those with less positive self-perceptions of aging.”

Even more remarkably, the study found that self-perceptions of aging had a greater impact on survival than other baseline factors, including gender, socioeconomic status, loneliness, and functional health. In fact, having a positive self-perception of aging provided a greater survival advantage than traditional health factors like low blood pressure, low cholesterol, healthy body weight, never smoking, or regular exercise.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that volunteering can help:

- Reduce disability

- Reduce mortality rates

- Decrease depression

- Increase happiness

- Improve quality of life

- Increase positive affect

- Increase purposefulness

- Increase physical activity

- Increase social connectedness

In the chart below, the upper case groups–indicated by M and F (green box)–are people who volunteer for at least two organizations. The lower case groups–m and f, (red box) are people who do not volunteer or only volunteer for one organization.

As can be see in the two older age groups, 75-84 and 85+, people who volunteer more frequently (M and F) have a lower mortality rate than the group who volunteers less or not at all (m and f). Although the difference in mortality rates did not quite reach statistical significance, larger meta-analysis, which combine the data of several studies, have found that there is a 25% reduction in the mortality rate for people who volunteer.

We again return to the publication “Impact of Healthy Lifestyle Factors on Life Expectancies in the US Population”.

This study define five “low-risk lifestyle factors”:

-

- Smoking: never

- Weight: healthy BMI=18.5 – 24.9

- Exercise: Daily, ≥30 min/d of moderate to vigorous

- Alcohol: moderate, Women 0.5-2 drinks/day, Men 0.5-3 drinks/day

- Diet: high quality (upper 40%)

In the below graph, we see that a 50 year-old woman (man) with zero “low-risk lifestyle factors” (i.e they smoke, and are overweight, and do not exercise, and drink too much alcohol, and has a poor quality diet) can expect to live an additional 29 (25.5) years. This is in distinction to a 50-year-old woman (man) who has all 5 healthy lifestyle factors (i.e never smoked, not overweight, exercises regularly, does not drink too much alcohol, and has a good quality diet) can expect to live an additional 43.1 (37.6) years.

The steel-blue dotted line in the below graph, along the X axis, is the baseline, reflecting a person who has zero low-risk lifestyle factors, the least healthy life style, i.e. they smoke, are overweight, never exercises, drinks too much alcohol, and has a poor quality diet. The other colored lines reflect the incremental longevity of a person with a more healthy lifestyle habits as compared to somebody who is living the most unhealthy lifestyle.

For example, on the left-hand side is the graph for a female. The vertical blue arrow shows that a 55-year-old woman who is living a very healthy lifestyle (5 low-risk lifestyle factors) will live about 13 years longer then a 55-year-old woman who has zero low-risk lifestyle factors. If this 55-year-old woman had only three low risk factors, her incremental longevity compared would be about seven years.

The graph on the right shows that the corresponding incremental longevity for 55-year old man (purple arrow) are 11 years and 6 years.

Finally, the graph below shows the probability that a 70-year-old male physician will survive to the age of 90 based on the presence of the specified unhealthy lifestyle factors including: sedentary, high blood pressure, obesity, diabetes, and/or smoking.

Clearly, a person who lives a healthier lifestyle will, on average, live longer than the person who is living a very unhealthy life.

If you made it this far and found the information useful, confusing, incomplete, or in error, please drop me an email.

Hayward Zwerling, M.D. (retired)

19 December 2024

1/15/2025 addendum: Add a graph to the exercise section.

1/24/2025 addendum: Added graph to exercise section.

2/13/2025 addendum: Updated Longevity vs Heathcare Spending graph